Understand mental health in high stress jobs

If you work in a fast‑paced, high‑pressure environment, protecting your mental health in high stress jobs is not a luxury. It is part of staying safe and effective at work. Long hours, constant deadlines, and emotionally demanding tasks can gradually wear you down if you do not have the right support and habits in place.

The World Health Organization defines workplace stress as a response to work demands and pressures that exceed your knowledge and coping abilities, especially when you also face poor job design, unsatisfactory working conditions, or a lack of support from colleagues and supervisors (Indian Journal of Medical Research). Over time, this kind of stress affects both your mind and your body.

How chronic stress shows up

Signs that your job stress is starting to affect your mental health can include:

- Trouble sleeping or waking up exhausted

- Feeling constantly on edge, irritable, or overwhelmed

- Headaches, stomach issues, or frequent minor illnesses

- Difficulty concentrating or making decisions

- Loss of interest in things you usually enjoy

- Turning to alcohol, food, or other substances to cope

Workplace stress is linked to serious mental health problems like anxiety disorders, depression, and substance use disorders (OSHA). It is also associated with physical health issues such as hypertension and diabetes (Indian Journal of Medical Research).

If you notice these signs, it does not mean you are weak or failing. It means your environment is putting more strain on you than is healthy, and it is time to adjust how you work and how you care for yourself.

Why high stress jobs are especially risky

Some occupations demand a very high level of stress tolerance. Jobs that require you to stay calm under pressure, accept frequent criticism, or face traumatic events, such as many healthcare and emergency roles, tend to carry greater risks for mental distress (American Psychiatric Association). Workers in health, humanitarian, or emergency roles are at an elevated risk of exposure to adverse events that can negatively impact mental health (WHO).

More than half of the global workforce, especially those in informal or poorly regulated jobs, often work long hours in unsafe conditions, which undermines their mental well‑being (WHO). Even if your job is not physically dangerous, constant deadlines, long shifts, or unclear expectations can have a similar effect on your stress levels.

Know your specific workplace risks

Protecting your mental health in high stress jobs starts with understanding the particular risks in your role and organization. Not all stressors are obvious. Some are built into your schedule, your workload, or your relationships at work.

Common risk factors to watch for

Researchers have identified several workplace factors that contribute to poor mental health:

-

Excessive workload and long hours

Long, unpredictable shifts and constant overtime make it hard to rest and recover. Psychosocial risks include work schedules that leave little room for sleep or personal time (WHO). -

Lack of control or autonomy

Having little say in how you do your work or prioritize tasks is linked to higher distress. In contrast, more control is associated with lower levels of burnout and better psychological health (PMC – NCBI). -

Poor job design and unclear roles

When your responsibilities are vague or constantly shifting, you may feel like you can never do enough. The WHO notes that poor job design is a core contributor to workplace stress (Indian Journal of Medical Research). -

Harassment, bullying, and discrimination

Sexual harassment and workplace bullying significantly increase stress and disproportionately affect women and people lower in the hierarchy (Indian Journal of Medical Research). Two‑thirds of employees who had experienced depression reported discrimination at work or during job applications in one cross‑country study (Indian Journal of Medical Research). -

Lack of support from supervisors and coworkers

When you feel isolated or fear criticism, every challenge feels harder. Positive aspects such as feeling useful and having supportive coworkers are linked to lower distress levels in many occupations (American Psychiatric Association). -

Exposure to trauma or adverse events

High‑risk roles that include witnessing injury, conflict, or crisis can increase your risk of psychological distress over time. A 2023 study found that psychological distress increases with each additional year in certain high‑risk jobs (American Psychiatric Association).

Quick self‑check: your job stress profile

You can get a clearer sense of your own risk by asking yourself:

- Do you regularly work overtime or skip breaks to keep up?

- Do you feel guilty or anxious when you are not working?

- Are your responsibilities clear, or do they change without explanation?

- Do you feel safe from bullying, harassment, or discrimination?

- Can you talk openly with your supervisor about workload and stress?

- Do you feel that your work is appreciated and useful?

If you answered “no” to several of these, your job may be putting you at higher risk for mental health problems, and it is worth taking deliberate steps to protect yourself.

Build personal coping strategies that actually help

You cannot always change the nature of a high‑pressure job overnight, but you can change how you respond to it. Evidence based strategies can increase your resilience and reduce the toll of stress on your mind and body.

Strengthen your day‑to‑day routines

Small, consistent shifts in your daily habits often matter more than occasional big changes. You can start with:

-

Sleep as a non‑negotiable

Try to keep a regular sleep schedule, even if your shifts vary. Create a short wind‑down ritual, such as dimming lights, turning off screens, and doing a few stretches before bed. -

Movement throughout the day

Physical activity is one of the most effective tools for managing stress. Even short walks, climbing stairs, or a 10‑minute stretch break can help reset your nervous system and reduce tension (Indian Journal of Medical Research). -

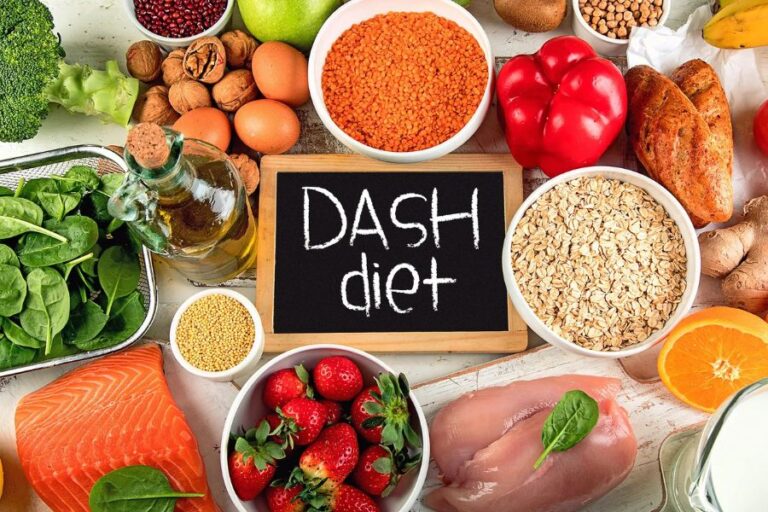

Simple nutrition anchors

In high stress jobs, it is easy to rely on caffeine and snacks. Aim for a few simple rules, such as having some protein at each meal and carrying a water bottle so you stay hydrated. -

Boundaries around availability

When your work is intense, true off‑time is vital. If possible, avoid checking work messages during your rest periods, and let coworkers know when you are offline so you can actually recharge.

Use mental tools to manage pressure

Interventions rooted in cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) have been shown to help workers manage stress more effectively (Indian Journal of Medical Research). You do not have to be in formal therapy to borrow a few of these tools.

You can try:

-

Naming the thought

When you catch yourself thinking “I will never catch up” or “I am terrible at this,” label it as “a stress thought” rather than a fact. This small step helps you gain distance. -

Reframing the story

Replace all‑or‑nothing thinking with more balanced alternatives. For example, “Today is harder than usual, but I have handled busy days before and can ask for help if I need it.” -

Breaking tasks into smaller pieces

Big, vague tasks keep your stress system on high alert. Divide them into steps and focus on one small, specific action you can take right now. -

Brief grounding exercises

When you feel overwhelmed, try a one‑minute reset: notice five things you can see, four you can touch, three you can hear, two you can smell, and one you can taste. This brings your attention back to the present and can lower your immediate stress response.

Protect yourself from burnout over the long term

Burnout is more than just feeling tired. Among mental health providers, studies have shown that 21 to 67 percent experience high levels of burnout symptoms like emotional exhaustion and feeling detached from their work (PMC – NCBI). Severe burnout is associated with a much higher risk of major depressive disorder and increased physical symptoms, including flu‑like and gastrointestinal issues, as well as higher substance use (PMC – NCBI).

To reduce your own risk of burnout:

- Give yourself permission to rest before you are at your limit

- Notice early warning signs, like cynicism, emotional numbness, or frequent irritation

- Rotate away from the most intense tasks when you can, even for short periods

- Take your vacation days instead of “saving” them indefinitely

If you are already feeling burned out, consider talking with a mental health professional who can help you develop a recovery plan and explore changes at work that might be necessary.

Shape a healthier work environment

Your personal habits make a difference, but they are only part of the picture. Because workplace conditions play such a large role in mental health in high stress jobs, it is important to look at what can be adjusted around you as well.

Use your voice to advocate for change

Workplaces are important venues for improving mental health and well‑being. Employers can help by reducing stressors, building coping supports, and connecting workers to resources (OSHA). In one survey, more than 85 percent of employees said that actions from their employer could improve their mental health (OSHA).

Depending on your role and comfort level, you might:

- Raise specific issues with your manager, such as unrealistic deadlines or chronic understaffing

- Suggest practical fixes, like rotating shifts, clearer role definitions, or improved communication channels

- Join or form employee groups that focus on well‑being or safety

- Share information about existing guidelines or protections for safety and harassment, especially if you work in a setting where these issues are common (Indian Journal of Medical Research)

Even small changes, such as adding a short debrief after intense events, can help normalize conversations about stress and give everyone a chance to reset.

Encourage supportive relationships at work

Positive social connections buffer you against stress. Research highlights that feeling useful and having supportive colleagues are linked with lower levels of distress (American Psychiatric Association).

You can:

- Check in with coworkers after difficult shifts

- Share simple coping strategies that work for you

- Offer and ask for help instead of struggling alone

- Practice small acts of appreciation, like thanking a colleague for stepping in or acknowledging good work in a meeting

These small moments build a culture where it is safer to speak up about stress and mental health.

Promote practical organizational supports

Effective interventions for mental health at work often combine individual support with organizational changes, such as increasing employee control and improving communication (PMC – NCBI). While you may not control policy decisions, you can still encourage options like:

- Flexible working arrangements where possible, which help manage psychosocial risks tied to work schedules (WHO)

- Clear frameworks against workplace violence and harassment so everyone understands what is unacceptable and how to report it safely (WHO)

- Access to mental health resources, such as counseling services, peer support groups, or stress management workshops

The World Health Organization notes that for every dollar employers spend on treating common mental health issues linked to workplace stress, they may see a return of four dollars in improved health and productivity (OSHA). That kind of data can be useful if you are making a case for better mental health support at your organization.

Use professional help and resources wisely

Taking care of your mental health in high stress jobs sometimes means involving professionals and using workplace programs that are already available to you.

When to consider seeking help

It can be difficult to know when “normal job stress” has become something more. You might reach out to a mental health professional if you:

- Feel sad, anxious, or hopeless most days

- Have trouble doing your usual tasks at work or at home

- Notice changes in appetite, sleep, or energy that last for weeks

- Rely more and more on alcohol, medication, or other substances to cope

- Have thoughts that you would be better off dead or that you want to hurt yourself

A therapist, counselor, or doctor can help you understand what you are going through and suggest options for treatment or support that match your situation.

Navigate workplace mental health programs

Some workplaces offer employee assistance programs, counseling services, or training for managers in recognizing mental health concerns. The WHO recommends training supervisors to notice mental health conditions and act early so workers get better support (WHO).

You can:

- Ask your HR department, union, or supervisor what mental health resources are available

- Use short‑term counseling services if they exist, even for a few sessions to get some direction

- Attend stress management or resilience workshops if they are offered

At the same time, routine mental health screening for all workers is not generally recommended, because it can lead to false positives and may increase anxiety without improving outcomes (Indian Journal of Medical Research). Instead, a comprehensive approach that reduces stressors, builds coping supports, and ensures access to help when needed is more effective (OSHA).

Plan for time away and returning to work

If your mental health has already been significantly affected, you might need time away from work to recover. Problem focused return‑to‑work programs, which look at both your health and your job demands, can make this process smoother (Indian Journal of Medical Research).

You can work with your healthcare provider and employer to:

- Set realistic expectations about what you can handle as you return

- Adjust your duties temporarily to reduce exposure to the most stressful tasks

- Schedule regular check‑ins to review how you are coping and what might need to change

Handling this thoughtfully reduces the chances of sliding back into the same level of distress that led you to take leave in the first place.

Put it all together in your daily life

Mental health in high stress jobs is shaped by both your personal habits and the environment you work in. You do not have to change everything at once to make a real difference. You can start with one practical step in each area:

- At the personal level, choose a small daily routine to protect your energy, such as a consistent bedtime or a short walk after your shift.

- With coworkers, reach out to one person you trust and agree to check in on each other regularly.

- In your organization, identify one change you would like to see, such as clearer expectations or better debriefing after difficult events, and bring it up with a supervisor or HR.

High pressure work will probably always involve some degree of stress. With the right supports and strategies, you can keep that stress from becoming a constant threat to your well‑being and instead build a career that challenges you without overwhelming you.